Conception

During the late 1700’s and early 1800’s, the potential of the area along the Peace River came to prominence when the explorers and fur traders arrived. Hudson’s Hope was an integral part of that industry. As the fur trade dwindled in the mid 1900’s the town settled down to ranching and logging. However, it wasn’t long before increased economic development in the populated areas further south raised the demand for electricity and the idea to use the natural water resource of British Columbia’s rivers was considered. The amalgamation of BC Electric and the BC Power Commission, overseen by Gordon M. Shrum, culminated in the creation of the Crown Corporation BC Hydro.

The Peace Canyon was the only un-navigable part of the Peace River system, requiring portage around its turbulent waters that dropped 215 feet in 20 miles. The mountain of sand, silt and gravel that comprised a glacial moraine, left behind 15,000 years before, blocked the original path of the river. Consequently, the river carved a new route around Portage Mountain through the rock formation of the Peace Canyon.

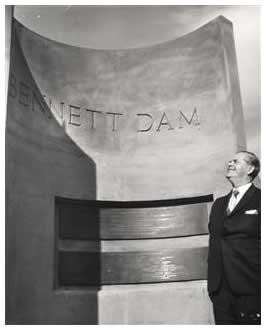

W.A.C. Bennett, (B.C. Premier 1952 – 1972) was not going to let this natural resource go untapped. Before the decision was made to build the dam at the head of the canyon, hundreds of soil and geological tests were undertaken. These masses of figures and drawings made up one of the largest feasibility studies in the world.

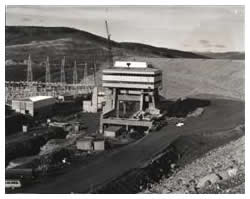

Originally named the Portage Mountain Dam, the W.A.C. Bennett Dam and the G. M. Shrum Generating Station were among the first and most ambitious of the hydroelectric projects built during the 1960`s and 1970`s.

Construction

The moraine provided the answer to constructing one of the largest earth filled dams of its kind. Three years of survey and study of data climaxed in plans to build a dam near the head of the canyon and to use the materials of the moraine to build it.

Construction of the dam took approximately five years and employed more than 4,800 people at its peak. By 1963, at a cost of $18 million, three tunnels had been blasted through a bend in the canyon wall to divert the river. These tunnels were immense and lined with concrete.

A low coffer dam was constructed to direct the water into the tunnels allowing the dam to be built on the dry river bed. However, a second coffer dam had to be constructed to hold back the rising spring waters. This structure ran 1,110 feet across the river channel to a height of 130 feet, and would later become part of the main dam.

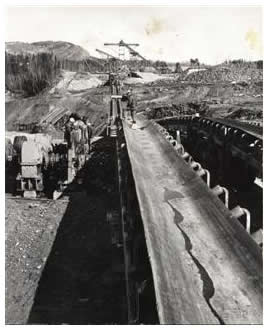

In 1964, construction on the dam itself began. D-9 Cats with giant blades bulldozed the moraine material into hoppers for sorting.

Graded material was then transported to the dam site by shuttle conveyors. The main conveyor was 66” wide and stretched 4.8 kilometres, making it, at the time, the longest continuous conveyor in the world. It moved at 12.5 miles/hour and was driven by four 850 hp motors delivering 12,000 tons of material per hour for screening and washing at the dam site. When completed, the dam measured 0.8 kms wide at its base.

A complicated conveyor system adjacent to the dam site mixed the moraine according to rigid specification for different zones of the dam.

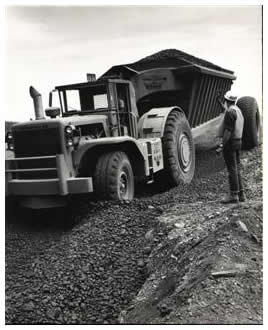

Dump trucks carrying 100 tons of earth rattled through the dam site.

These trucks poured over 57 million cubic yards or 100 million tons of gravel, sand and rock over the course of the construction of the dam.

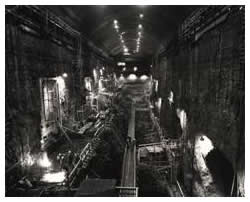

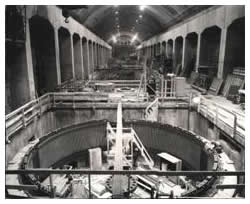

At the same time, work was being done to construct the power house deep within the east abutment out of the solid rock of the canyon wall. This massive chamber would house the hydroelectric generating facilities of the dam.

Meanwhile deep underground, crews continued to pump concrete at measured pressures into the minute crevices of the foundation of the dam.

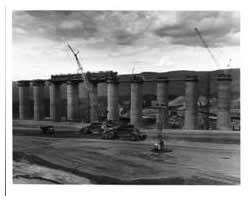

By the spring of 1967 the intake towers that would admit water into the subterranean powerhouse were nearing completion. The dam had now reached an elevation 450 feet above the riverbed with only 150 feet to go.

Across the valley the spillway channel had been gouged out of the rock to provide an escape route if the reservoir ever threatened to overflow. This discharge channel is lined with concrete and extends 2,300 feet from the crest of the dam to a point 250 feet above the downstream riverbed. When opened, it can allow 9,205 cubic metres of water per second to be launched into Dinosaur Lake below. This spectacular sight draws hundreds of visitors when it occurs every few years.

By July, the structure of the dam was nearing its final crest line. Meanwhile turbine components began arriving in Vancouver for transportation to the project where, deep down in the rock, the first five penstocks were ready to be connected to the power generating equipment. During construction, the framework was put in place to enable expansion of the generating capacity of the dam. Over the years, five more generators have been added. Large contracting companies are now back in town upgrading the generating units.

Two massive tunnels lined with concrete were built to allow spent water to exit the dam and rejoin the river once more.

Over 574 miles of 500,000 volt transmission lines were laid from the dam site to the lower mainland via Prince George and Kelly Lake. Nearly 7,000 miles of aluminum cable conduct the power into the grid system.

Completion

On September 12 1967, a ceremony was held where Lieutenant Governor General George R. Pearkes dedicated this enormous dam to the service of the people of British Columbia.

The Williston Reservoir was continuing to fill and would eventually stretch 300 kilometres to a maximum depth of 175 metres.

On September 22, 1968 over 3,000 people jammed into the huge underground power house to watch the premier switch on Peace Power.

The final cost of construction was approximately $700 million and another $200 million for the transmission lines.

On September 28, 1968, power from the project was generated for the first time.

Now 40 years old, the W.A.C. Bennett Dam and G.M. Shrum Generating Station remain among British Columbia’s most outstanding engineering achievements.

Impact

Such a major project will inevitably impact the area. A once peaceful village became the hub of economic and social change. The initial influx of workers, many from Europe, raised the population in 1966 to 5,500. As Shirlee Smith Matheson remembers in her book, This was our Valley, when she first walked into the Peace Glen Hotel, “ I looked out at the bar, and 300 pairs of eyes stared back. Then I realized there were only five women in the entire room. The scene was like the Klondike Gold rush – men with money, and nowhere to spend it. Working men from all over the world were here, making wages they’d never dreamed of, building the largest earth-filled dam in the world.” Once union issues had been resolved, local people were employed during the constructions years and some families have continued maintaining and operating the dam.

Hudson’s Hope was not incorporated until 1965 when it became the second largest municipal district in B.C. covering 360 square miles. Trailer courts sprung up and BC Hydro built town houses for its managers and contractors. By 1968, roads had been paved and a new Municipal Office and Fire Hall had been constructed. However, for some, things were moving too fast.

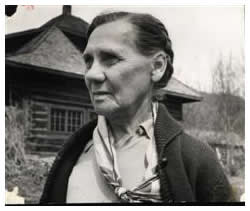

The construction of the dam impacted far more negatively on the people living upstream. First Nations and residents of the valley and its tributaries, the Finlay and Parsnip, were re-located. Mrs. Beattie’s face says it all as she left her Gold Bar Ranch, 20 miles north of the project, for the last time before it was set alight. She had had indoor plumbing for decades in her substantial ranch house where she and her husband had raised their 8 children. The family had cleared hundreds of acres of land that would soon be lost forever. In all, 1,773 square kilometres of resource rich land was flooded.

The waters rose more quickly than anticipated and little of the harvestable timber was logged and utilized. Local freight and guiding businesses could no longer use their river boats for transportation on the quickly expanding Williston Lake. Once the dam started generating power, the Peace River downstream remained open as far as the Alberta border. The natural rhythm of the Peace River was forever changed, so its levels now fluctuate depending on power needs not on the usual freeze/thaw cycle.

BC Hydro continues to address issues such as dust control from the sloughing river banks and debris clean-up. The Peace/Williston Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program was put in place in 1988 to conserve and enhance fish, wildlife and their habitat in the watersheds of the Williston and Dinosaur reservoirs.

Now, 40 years on, Hudson’s Hope is regarded as a quaint and unique town with a steady population of 1100 people, many of whom are BC Hydro employees. Residents benefit from the excellent sporting facilities and a modern K-12 school. A doctor and three RCMP officers look after the welfare of the community. Local businesses and camp sites benefit from the 12,500 tourists who visit the W.A.C. Bennett Dam each summer and take guided tours down into its depths and drive across its crest.

Quick Facts

W.A.C. Bennett Dam:

- Length: 2 kilometres

- Width: 800 metresHeight: 183 metres

- Capacity: 2,730,000 kilowatts

- Spillway:

- Length: 850 metres

- Width: 30 metres

- Capacity: 9,205 cubic metres per second

Williston Reservoir:

- Name: Named after Ray Williston, member of provincial cabinet in the 1960’s and early 1970’s

- Size: 1,773 square kilometres

- Length: 300 kilometres

- Max. Depth: 175 metres.